Dorothy Pauline Brown - The Daughter

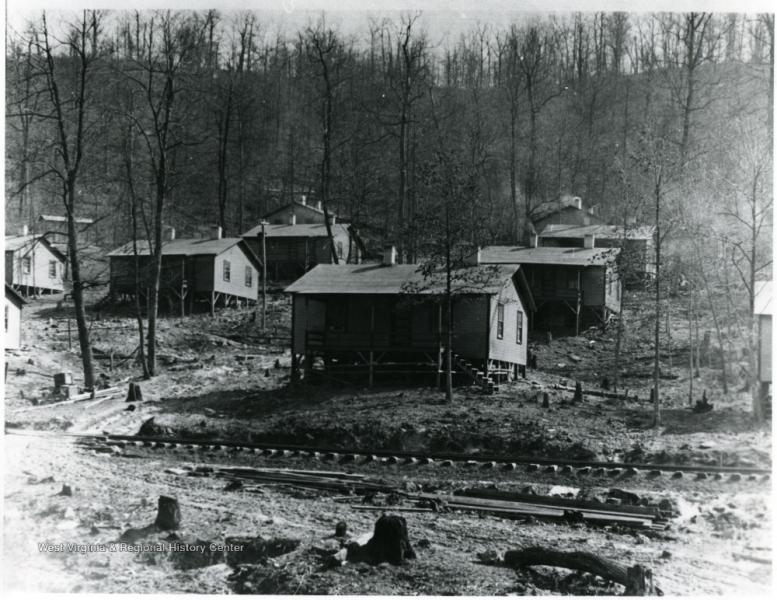

I was born somewhere in Sullivan County, Indiana. All eleven of us kids (Verdie, me {Dorothy Pauline}, Kenneth James, Lucy Elizabeth, Gilbert VanHorn, Violet Rosetta, Danny, Darrell, Edna May, Connie and Paul) were born at home. Mom and Pop and the eleven of us lived in a 4-room cinder block house. Our house looked like all the other houses because they were company houses. The company or coal mine owned the houses, and the stores and we knew we belonged to them. Everyone knew everyone else. We never lived anywhere else but in a mining camp or ‘the blocks,’ as everyone called it. We didn’t have electricity – just oil lamps. We didn’t have a pump, or plumbing, everything was outside. We didn’t have tubs or showers. When Pop came home from the mine, he was covered with black stuff. Pop would use a big white dishpan to wash up in when he came home. That was his bath. We heated our stove with coal and heated him some water.

When the coalmine whistle blew each evening, we knew to go home. My mother, Ada, stayed at home to raise us eleven children. We had straw ticks for mattresses. We would split them down the middle and put straw in each corner and then stuff the middle part. I think most of us shared one bedroom. We just laid crossways in the bed. We were poor, but we were clean. Mother had bare floors and she would scrub them with lye until they were white. When I got older, I use to polish the little one’s white shoes. I set them around the stove to get dry.

In the winter, if we left the water in the pan setting in the kitchen over night, it would be frozen in the morning. Pop would buy groceries at the mining store and he would carry that big load of groceries (large cans of lard and big sacks of flour) over his shoulder. My dad would get up about 4 a.m. to go to work. My older sister, Verdie, and I would take turns getting up with Pop a lot. We knew we had to get up when he said or he would come in there and whop one of us. My sister would pinch me because she knew I would get up. I got Pop’s breakfast and fixed his lunch bucket. I pretty much raised the other kids. Pop walked to work every day, regardless of the weather.

We ironed everything. We ironed with handles that clipped on the iron. The irons set on the stove. Sometimes the iron heat up so much you had to have a pad to hold them. I even ironed the baby’s diapers. I did all the work but Pop always helped with the washing. We had a large fire and put the big lard can on it and put soap in it. We pushed our clothes around with a broom handle. We had two tubs and I would rub the clothes in one and rinse in another. My Pop was the best washer around. His clothes were white as snow. We put them in rinse water with a little bluing and hung them on the line. My mother would never undress in front of her husband. Mother would go behind the stove and get dressed.

FOOD

For food, we had beans, fried potatoes, tomatoes from our nice garden, and if mom felt like it, she baked pies or cakes. We had a cool off stove that was an oven you set on the burners. It was a coal oil stove. I could make pies in it. When we lived in the blocks, we had to build a fire and keep it going. When we ate dinner, there were not enough plates for everyone. One of us kids ate out of a pie tin and someone ate out of the top of Pop’s lunch bucket. We had silverware and we were just glad everyone had something to eat. We had oatmeal for breakfast and hot water in milk and sugar. We never had bacon, eggs or other cereal. For lunch we had beans, one kind one day, one kind another.

Grandpa Ammerman, my mother’s father looked like Abraham Lincoln. He was a great carpenter. He made a long stool and it set behind the table. As the kids got older they went from the stool to the chairs. The coal miners would go on strike during the summer. They lived well in the winter and starved in the summer. Even with eleven kids, we never went on welfare. My dad could get clothes for kids at ‘Shelburne’ during the depression. They called it the ‘graboff’ and Danny hated those clothes. Everybody else was poor, so we didn’t think about being poor. We never had a telephone. My parents really never knew what it was. My grandmother had one, though. We had a big, battery radio when we lived in the blocks. It had more news and talk shows. We did not take a newspaper because we couldn’t afford it. We didn’t have cupboards; we kept our pots and pans on the stove. I had a big, old safe that our cupboard. I painted it, my chairs, and the high chair a different color every year. My floor was pink linoleum.

HOLIDAYS

We saw relatives and cousins that lived near by for family gatherings. Grandpa Ammerman lived in Farnsworth down near Sullivan. Everyone brought a dish and we had a good time. For birthdays, we didn’t do anything. I never had a Christmas tree for my kids. We didn’t know what Christmas was when I was growing up. We would hang our socks up in the living room. Pop was a real teaser and one time he put coal in my sister’s sock. We didn’t get toys and things, we might get an orange or a banana, but we were poor. I went to church for the first time with my grandmother. A neighbor took me to the Church of Christ, that’s where everyone is buried. The church is gone now.

TRANSPORTATION

Once we moved from one company house to another back in the woods. We walked four miles from ‘the blocks’ where we lived to Stop #23 where the streetcar stopped. The streetcar was a regular trolley with wires on top. I sat on the end seat so I could see what was happening outside. We had a two-seater carriage. Our horse was named old babe and we could hardly get her up. When Emerson, a fellow I dated, got a new buggy, I thought I had it made. We didn’t have a car for a long time. I learned to drive on a car with a crank. My son, Billy, and I learned as he sat on my lap and I drove in Sullivan. One time I was driving Pop into town and we were going down a hill and we went into a ditch. Pop said, “Who said you could drive?” When I lived on Addison, in Indianapolis, we used the trolley cars. We had to use transfers to go from one trolley to another. It was nice.

RACE RELATIONS

There were a few blacks in Sullivan, but you didn’t know they were any different. They were nice and treated just like everyone else. They didn’t eat separate; the children ate together and played together. Elsie and George, who had a barbershop in his house, were the best friends I ever had. When Pete, my first husband, was in one of his moods, I would go to their house and stay all night. There was one black man who had a convertible and every time he went by the house, he would tip his hat at me.

ENTERTAINMENT

Mom and Pop went fishing for entertainment. They went to ‘the Bayou,’ ‘the Cutoff’ and other coalmine ponds. They fished for everything they could catch. We ate them all. He would bring them home by the tub full. My favorite thing was going to the movies, the Sherman and the Lyric. They were the only movie houses in Sullivan. We went to Hymera, a city nearby, to see what was there. We went to carnivals in Sullivan but Pop didn’t want us to go. Grandma lived in between the carnival and the streetcar line. Verdie and I told Pop we were going to Grandma’s but we went to the carnival. Pop was waiting on us when we got home. He really got us told. He wanted us to stay home. I took my mother to the first talkie in Sullivan at the Lyric. There wasn’t much else to do.

ILLNESS AND DEATH

We experienced a lot of death during my childhood. There were lots of old people. They didn’t live very long. All of us were delivered at home. The doctor came when he could by horse and buggy. Pop went to the neighbor or sent one of us kids to get a phone. Mom was sick a lot. She had a baby every 16 months. She had a pain in the top of her head all the time. She kept a bag of ice on her head and a scarf tied around her head. Pop even took her to Indianapolis once but they didn’t know what the problem was. She died of lung cancer and never smoked a day in her life; however, she did chew tobacco from the age of seven.

The worst memory of childhood was when my little brother, Paul, who was 18 months old, died. No one ever knew what it was. Kenneth and he had made a tent in the hot sun. Pop wasn’t home. Grandma wasn’t home, she was out berry picking so we couldn’t get to a phone to call anyone. Verdie and I just layed down on the grass and cried and cried. Mother took it awful. She ran over to a big hole and Pop caught her. If he hadn’t stopped her, she would have thrown herself in. When little Paul died, my dad took it so bad he couldn’t go back to work for a while, he couldn’t take it. Every day little Paul would meet him after work. The bottom of his dinner bucket had water in it and the top had food. Pop would save something for little Paul. He would give little Paul his dinner bucket and Paul would eat the little food that was left. That night Pop said to kiss Paul good night and his face was beginning to get hard. There was no embalming.

When Uncle Ross, my dad’s brother, was killed by a streetcar while walking home from Shelburne, they laid him in the parlor. There were singers who wore white gloves that went above the elbow. The dead were taken from the home to the cemetery. For little Paul’s funeral, Verdie and I sat in the back seat and held that little coffin on our laps all the way to the cemetery. After the funeral everyone came back to grandma’s house to eat. Danny was 13 and in high school when he died of colon cancer. One of the flower arrangements was shaped like a wheel with 13 spokes, but one was broken. We had his funeral at home, too. He was dressed in his usual white pants and I combed his hair the way he like it. He lived six months from the day he was operated on. He knew he was dying but he told mom he was going to get well. He said, “I’m going to build a ladder that will take us to heaven.”

Grandma Ada, my mother’s mother, died when baby George was born. He was born tongue-tied and his feet together. He was retarded but he played with us kids. When we ran around the house, he would run around with us. George would come down to borrow something for grandpa. We would mention a lot of things and when we came to the thing he wanted, he would say, “Yeah! Yeah!” They finally put him in a home in Sullivan.

CLOTHES

Mother, when able, made the little ones clothes. Outing flannel dresses even for the boys. When little Paul died he wore this little flannel dress. She made me a percale dress and she trimmed it in rickrack. I thought I was really something. My sister, Verdie, didn’t care whether she had runs in her stockings like I did. Verdie wanted to borrow my girdle and I wouldn’t let her, so she burned it up. One time I bought myself a pair of black, patent leather oxfords. I had to use a buttoner, a long hook to button my wedding shoes. My wedding dress was brown tricolette. I borrowed $2 from my grandmother to buy a brown hat. I spent my money on clothes. I bought me a blue taffeta dress once. It wrinkled easily. I pressed it so much it split.

GAMES

We played dandy-over. One child would take a baseball, with one team on one side of the house and another team on the other side and throw the ball over the house. Whoever caught it, won the game. Stepping on wood was a game that if you stepped on a piece of wood you were fined. We also played hopscotch. All the boys and girls played together.

SCHOOL

I loved school. We had to walk several miles to school. When my mother had Violet, Pop took the baby over to Grandma Brown’s because Mom had the flu. Grandma Brown, my father’s mother, didn’t take very good care of the baby and Grandpa Brown didn’t like it. Pop took me out of school then. I was in the 7th grade. Back then you had to take an examination and write to go to high school. My sister took the test three times and didn’t pass. She quit school and got married right away. I loved school and I made good grades. I was only 12 or 13 when I had to leave school.

The schoolhouse was a one room, brick schoolhouse. I was the teacher’s pet. The kids didn’t like me because I was the teacher’s pet. The classroom was full. We used to have spelling bees and I could spell all the students down. We all learned to read and write. We had geography, history, arithmetic, and reading. I wished I had gone back to school. I got married early so I didn’t get to go back to school. I always wanted something better. We were comfortable but I wanted nice things.

WORK

I worked down in Sullivan on millionaire’s row. I was a maid. I made between $5.00-$7.00 a week and I could eat and live there. I didn’t eat at the table with them. We would eat in the kitchen. I saw an ad in the paper for a job on the west side with Dr. Graddy. I had to clean his big house, do all the cooking and clean Dr. Gaddy’s office, too. I never got any complaints. When I went to Chicago, I was my sister, Lucy’s, maid for a short while. Everyone moved from Sullivan to work at the Benjamin Franklin Factory. They sent money back to the folks. It was work that caused them to leave. Edna worked all of her life at RCA and retired from there.

Even when I had my fourth child, Ada Jane, I went and cleaned people’s house. They paid me $8 a day and it took me all day. Often I worked for some of the women from church. I also took care of other people’s children. We never got rich, but we lived a nice life.

DATING AND MARRIAGE

My dad said I was too young to have dates. I was 16 and my sister was 17. Pop thought I was too young. When I met this fellow Emerson, he lived on a farm. I knew Pop wouldn’t let me go. My sister, Verdie, and her boyfriend came by one night with Emerson hiding in the buggy. Pop knew something was up. After a while he let me date Emerson.

1922

The kids’ dad, Pete

I met Pete, the kid’s dad, when I was taking Danny to the doctor in Sullivan. Streetcars turned around in front of the pool hall and there was Pete standing in the doorway. Pete was a clerk in the poolroom. Danny and I went to the doctor’s. Pete saw Danny and I coming back and he got on the streetcar and gave Danny a candy bar. Pete lived with his dad until he got a stepmother. Their house was an old shotgun house with very wide floorboards. Pete asked me for a date but he didn’t have a car. He walked from Stop #23 to Mildred Blocks, where we lived, to date me. I don’t remember what we did. We just walked around the hills and hollers. Grandpa Brown said that Pete told him if he couldn’t marry me, he would jump down the well. I was 17 and he was 18 when we married.

His folks lived at 333 W. Graysville, Sullivan, by the hospital. They built a house on the next lot. I helped them build the house. They didn’t treat me very good. Pete’s folks thought I was from across the tracks. They called where they lived the Owings addition. They had money. His sister, Dottie, worked at the Index. My parents didn’t care if I got married. His dad was with us when we got married by a Justice of the Peace. After Pete and I got married, he wouldn’t let my folks come for Christmas or anything. He was an Owings, a bad attitude, the same today as then. They were all grouchy. I didn’t let anyone run over me. He had another woman five years before I found out. They called it depot town and her name was Eva Pigg. He didn’t marry her.

1932

Divorce

He sued for the divorce in 1932. I cried for my kids, not him, I had lost all respect for him. I was up the crick without a paddle. I knew I had to leave the house with the kids. The boys went to Florie’s house. This Eva Pigg’s friend was a friend with my sister Lucy. While Lucy was there, Pete came over to see this Eva. He never paid the one cent of support.

I was a fanatic about cleanliness. Pete had his boss come down and see how nice our house looked. We had a well first and then a pump. I had Norma Jean, my second child, and the well had wooden curve. She kept putting her feet in it. I knew she would get into it. Pete’s uncle Charlie covered the well and built us a pump. I never had the screen unlocked until I saw what kind of mood Pete was in. But I am still sorry it didn’t work out for Pete and me. I am sorry for my children. But he didn’t change. People will remember me for my dust rag.

It ended up that my boys wanted to stay in Sullivan until they graduated from high school. Only Norma Jean came to me when she was thirteen years old. I don’t blame Pete totally, because my house and my kids came first. I really think I had a lot to do with it. We were married 10 years. There was no reaction from the towns’ people. My mom and dad were glad we got the divorce. One time Pete took a bucket of water and sloshed it all over my new wax floor. He took all of my clothes and threw them out the door. He was hitting me and I took my pan and almost beat him to death. If I hadn’t beaten him, he would have killed me. He didn’t drink, he was just mean. He had a terrible temper. His family hated the divorce because of the kids.

My sons, Billy and Bob, went to stay with Florie and Bo, their aunt and uncle. Billy would come by and see what I had to eat. If he didn’t like what I had he would go over to Florie’s to eat. Norma Jean stayed with Aunt Nell, an Owings, every summer. They were crazy about Norma Jean. The kids were afraid of their dad. He wasn’t mean to them. He never showed them any affection.

After graduation, Billy came to live with me in Indianapolis. If I had to do it over again, I would try to make things better to stay with my husband and my children. I always sent the kids money. I got them each a watch when they graduated. Neither family said anything when I had to go away. Bob came to Indianapolis for a short while but he didn’t stay. The kids liked living with Florie and Bo. Bob slept with Florie until he was 14 years old. Billy slept with Bo. When Bo died, Florie said it was worse for her when Bob left. They were so attached. The kids had it made there. They were 8, 6, and 4 when they went to live with these people. My heart was broken so many times for my kids.

Pete never saw the kids except to try and live with the people they were staying with. He then married Edith. She wasn’t the one he had an affair with. They had a child, Tommy. I saw him at Grandpa Owings’ funeral. Pete never came to see the kids after that. When Pete was dying, Tommy called Norma Jean and said, “Dad wants to see you.” Edith wouldn’t let them in when they went to Chicago. They hadn’t seen him in 20 years.

Eddie Young

Husband #2, Eddie Young, and I were married 5 years. He was from Vincennes, Indiana. We always lived in rooms and never had a home. He was a coal miner. I wanted more from life. Eddie’s friend was a lawyer and he helped us. Eddie got drunk and was put in jail. I couldn’t put up with that boozing. We never had a car. He always called me Buddy. He married a friend of mine, named Frankie.

1939

Bill Emery

I met Papaw or Bill Emery at his barbershop in the Ben Davis area of Indianapolis. The lady I was working for and taking care of her two children introduced us. There wasn’t enough room for everyone to sit in Olive’s beauty shop, so I sat in the barbershop. Olive said, “Dottie, there is the best looking barber in our first chair.” Norma Jean was living with me. The barber said to Ollie, “Who’s that lady?” Olive said, “That’s the girl who lives with me.” He said, “She has a good looking rumble seat.” It took him about six weeks to ask me for a date.

At that time he had an old Willy’s. I hated that old Willy’s. My knees touched the front of it. We went to Danville, Indiana and he got out and went to the drug store and bought a bottle of wine. He thought if he got me drunk, we would have a party. He got fooled. We parked some place where it was dark. I fought him all over that Willy’s until his wrists were black and blue and my knees were black and blue. He thought this old lady has been married and we would have a good time. I was engaged to Jim Swift at the time. When Jim came out to Olive’s I would lay down in the car so Bill Emery couldn’t see me. I was playing both of them. Jim’s mother was the only mother-in-law I ever knew. I was supposed to tell Jim if I was going with him or Bill. I told him I was going with Bill. He kissed me goodbye and said it’s been nice knowing you. That was it. He married after that and his new wife was so jealous. Jim was so crazy about me.

A Justice of the Peace in Louisville, KY married Bill and me. My sister, Lucy, went with us. We just drove down there to get married. Bill Emery and his first wife had been separated for years. Papaw was a ladies’ man. I didn’t break up the marriage. Eva, his first wife, lost her sight before she died. When his son died, Eva told me she lost both the men she loved. Bill’s son had two girls. Everyone from Sullivan liked Papaw. Papaw gave my Pop the last $50 to pay off his house rather than buy a dog. Pop had an attorney or something and they sold the house when he died. It is torn down now. There is a big tree there now.

1940

INDIANAPOLIS

I was 35 and Papaw (Bill Emery) was 40 when our daughter, Ada Jane, was born. She was our entertainment besides going to church. We had a TV, radio and car. While living in Indianapolis, we went to the movie and to Riverside Park. Norma Jean was with me then, and Olive’s brother, Skeeter, lived with us, too. Papaw (Bill Emery) and I were married lacking 2 months of 60 years. He died at 104. Papaw and I had Ada Jane, Norma Jean, my son Billy, my son Bob, his wife, Jo, and their kids living with us. Each family slept in one bedroom and they put their clothes in boxes under the bed. We got a long fine. The guys were in the service so the girls lived with me. They were all good, and they all helped. My brother, Darrell, even stayed with us. We didn’t have air conditioning, had only a window fan and it was an oil fan.

In Indianapolis, we had a coal stove and I had to take the ashes out. Papaw had just bought a load of coal but I had made up my mind I wasn’t taking those ashes out anymore. I had to do it all. Papaw didn’t do anything around the house. I even mowed the yard. I went to the west side of Indianapolis and I bought an oil stove that looked like a big television. Papaw threw a shoe because he had just bought a ton of coal. It was just delivered to the garage in back. Someone came every so often and filled up the oil. I just didn’t pay any attention to Papaw. We washed our porches down to keep them nice. I had nice rugs in the dining room and living room. I would get on my knees and scrub them.

Papaw Emery had a sister Clare and Goldie. We saw them and they were crazy about Ada Jane. Grandpa Emery would go to the door and he would ask us always where is my baby. She was afraid of Grandpa because he was old and didn’t get along too good. The three of us went to church every Sunday. The best thing that happened was when I married Papaw and I became a better Christian. Papaw became a Christian, too. Greatest thing was when I was baptized at 21 yrs.old.

When my son, Billy, came up after he graduated, I lived in Maywood, a small area outside of Indianapolis. Billy and I would go out in his car and drive and he would see if he could spell me down. Billy and I went together to the movies a lot. That’s how we entertained each other.

Papaw was gone every night and he went coon hunting. I made Ada Jane, our daughter, who he called Ada doodle daddle, wait for him to come home to eat. He was never home. One night I went to a church board meeting and Papaw was in bed sick. When I came home from church there hung two raccoons. I wondered who had brought those raccoons home to Papaw. He had gotten up out of his sick bed and caught him two raccoons. He sold them to the black people for money. They ate them. We didn’t eat them. I ate a possum once, but it tasted like fatty pork. My favorite thing to cook was pork chops and dressing.

SHOPPING

In Indianapolis, I had a milkman and a bakery man. They came by door to door. We bought our clothes ready made. Stores were like they are now. They were not big like we have now but they had an upstairs. You would take your purchase upstairs and then go downstairs and pay for it. They sent the money up on a wire to pay for it and then they gave you the stuff you bought.

GREATEST INVENTION

The greatest invention we have had in my lifetime? Well–I don’t care for the computers but I am real glad for electric lights. Whenever the wind blows here the lights go out and I am so glad for electric lights. I went on an airplane the first time 2 years ago. I couldn’t see the scenery because I can’t see too well now.

SOMETHING DIFFERENT

f I could do anything different, it would be to stay in the church. When I was married to Pete, I was baptized in the Christian church and I tried to live a Christian life. After our divorce, I didn’t go until Papaw and I got married. I was the President of the Mary’s Circle at the Methodist Church for 28 years. I was president of my Sunday school class. I did this until 1982, when we moved down to Brown County and my daughter, Norma Jean, passed away.

Recorded and written by

Karen L. Patton

Published U.S. Legacies December 2002

- Log in to post comments